Fancy reaching a wider audience and boosting sales without extending your dining room? Restaurant delivery apps certainly seem like the perfect solution, especially after the boom in online ordering during and after the pandemic. But are they really a silver bullet for growth, or a slow drain on your profits and brand? This guide walks through the upsides, the downsides, and the strategies that can help you decide how – and whether – to rely on third‑party platforms for your business.

The Rise of Delivery Apps: A New Era for Restaurants

Not long ago, takeaway meant a phone call, a paper menu and a driver who “knows the area.” Today, a few taps on a smartphone can summon food from thousands of restaurants on platforms like Uber Eats, DoorDash, Deliveroo, Swiggy and Zomato, depending on where you operate. Globally, online food delivery has become a multi‑hundred‑billion‑dollar market, with double‑digit annual growth in many regions, fundamentally reshaping consumer expectations around convenience and speed.

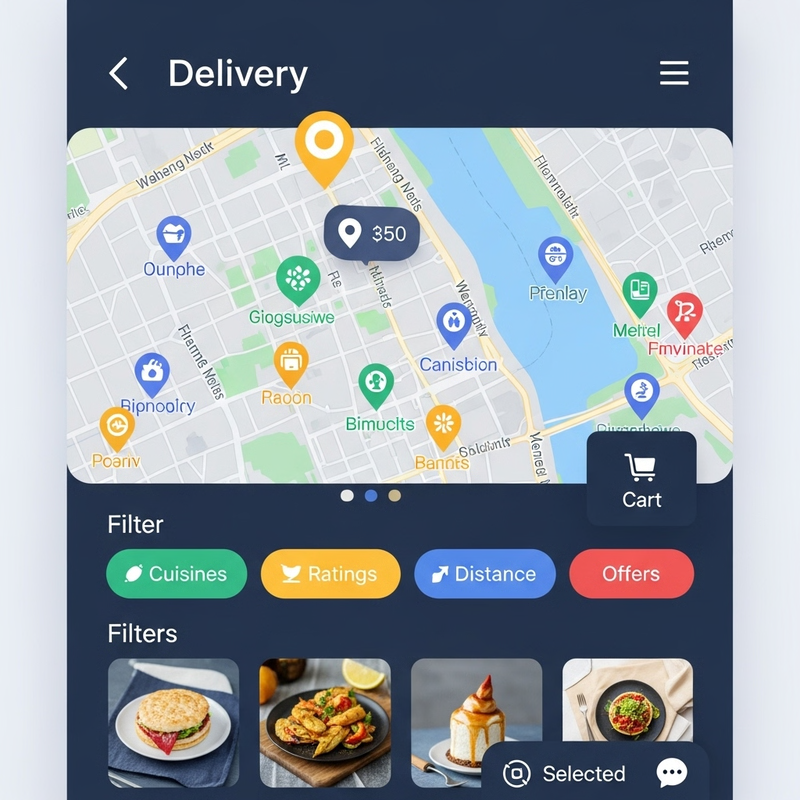

For restaurants, these apps represent a new layer of infrastructure: they handle discovery, ordering, and often delivery logistics, in exchange for commissions and fees. That shift has opened up opportunities for operators who might never have invested in their own dispatch system, but it has also created a new dependency on third‑party technology gatekeepers who control visibility, customer data and a growing share of revenue.

1. The Pros of Partnering with Delivery Apps

For many owners, the initial appeal of delivery apps is very real. These platforms act as a digital high street, putting your logo and menu in front of people who may never have walked past your front door. Strong in‑app search, filters and recommendation algorithms can surface your restaurant to nearby users at the very moment they are hungry and ready to order, which can translate into incremental sales, especially during slower periods.

The reach of these services often extends well beyond your natural catchment area, particularly where a platform has its own fleet of riders and established delivery zones. Because the app handles payment processing and – if you opt for their logistics – the driver network, you can launch delivery without buying vehicles, hiring drivers or building your own online ordering system from scratch, reducing upfront capital outlay.

Many platforms also bundle in marketing tools: sponsored listings, homepage banners, discounts, “featured” tags and email campaigns aimed at their user base. For a busy operator, plugging into these ready‑made promotional levers can feel like outsourcing a chunk of your marketing function, even if it comes at an extra cost on top of commission.

2. The Cons: Margin Pressure, Control and Competition

Once the initial bump in orders settles, the financial reality often hits. Third‑party delivery apps typically charge commission in the range of roughly 15–35 percent per order, depending on market, service level and negotiation, with some restaurant‑tech sources citing bands like 12–35 percent. In an industry where many independent restaurants operate on single‑digit to mid‑teens net profit margins, handing a quarter or more of each delivery ticket to a platform can turn busy evenings into break‑even or even loss‑making shifts.

There is also a meaningful loss of control. Once food leaves your kitchen with a third‑party courier, you no longer control handling, temperature, or the courtesy of the handover, yet the customer’s review usually lands on your restaurant page, not the driver’s profile. Late deliveries, leaking packaging or cold meals can damage your ratings and brand equity, even if your team did everything right on‑site.

Data is another sore point. On most major marketplaces, the platform, not the restaurant, “owns” the customer relationship in a practical sense: you see the order, but not the full set of contact data and behavioural insights that would allow you to build a direct CRM pipeline. That makes it harder to run your own loyalty schemes, email campaigns or targeted offers without going back through the app and often paying to boost visibility.

Competition within the app can also be brutal. You are listed alongside dozens or hundreds of similar restaurants, many willing to slash prices or pay extra for sponsored placement just to appear higher in search results. In such an environment, customers often browse based on discounts, delivery time and rating, rather than brand loyalty, which can commoditise your offering and force you into a constant promotion cycle.

Menu constraints add another layer. Certain dishes simply do not travel well: they lose texture, collapse in transit or arrive looking nothing like the carefully plated version you serve in‑house. That often forces operators to create a “delivery‑optimised” subset of the menu and re‑engineer packaging – sensible from an operations standpoint, but potentially limiting if some of your best‑known dishes are not suited to delivery.

Using Delivery Apps Without Letting Them Use You

The most sustainable approach for many restaurants is to treat third‑party apps as one channel among several, not the backbone of the business. One common tactic is to price items slightly higher on marketplace platforms than on your own menu to offset commissions, while curating the delivery menu around dishes with strong margins and good travel performance. Some operators also design bundle deals or family packs specifically for delivery, which simplify prep and keep food more stable in transit.

Negotiation is more possible than it first appears, especially if you are an established brand, multi‑site operator or can demonstrate high volume. Reports from restaurant‑tech providers and consultants note that some restaurants have been able to secure lower headline commissions or different fee structures by providing their own drivers or agreeing to some degree of exclusivity in return for better terms. While smaller independents may have less leverage, it is still worth asking platforms about tiered pricing, trial arrangements, or marketing credits before signing long‑term deals.

At the same time, many operators are investing in direct ordering channels – their own websites, white‑label apps or QR‑based solutions – to reduce dependency on marketplaces. Providers of first‑party ordering systems argue that this model allows restaurants to keep 100 percent of the order value after payment processing, fully own their customer data, and design loyalty schemes on their own terms, often for a flat monthly SaaS fee instead of per‑order commissions. By encouraging repeat customers to order directly, for example via in‑house discounts, loyalty points or exclusive menu items, restaurants can gradually shift a portion of volume away from third‑party platforms.

Brand consistency remains critical. Even when using multiple apps, ensuring that your name, imagery, menu descriptions and packaging all align with your core identity can help reinforce recognition beyond the marketplace context. Thoughtful packaging that keeps food secure and presentable, along with clear reheating or allergen information where appropriate, can also cushion some of the risks posed by third‑party couriers and improve the overall experience in the customer’s eyes.

Choosing Platforms and Preparing for What Comes Next

Not every app is equally suited to every restaurant. Some platforms skew towards fast‑casual and quick‑service brands, others have a stronger reputation for premium or independent venues, and local or regional players may offer better commission structures or support in certain cities. Evaluating where your target customers actually order, how wide a delivery radius a platform supports in your area, and how well it integrates with your POS and kitchen workflows can make a big difference to operational stress levels.

Behind the scenes, there is a noticeable shift toward models that reduce reliance on the big marketplaces. Ghost kitchens and delivery‑only brands continue to proliferate in some markets, using app demand data to optimise menus and locations, while at the same time many brick‑and‑mortar operators are doubling down on direct digital ordering as a hedge against rising fees. Industry analysts also highlight experiments with subscription‑style delivery passes, tighter regulation of fee caps in some cities, and maturing white‑label technology that allows even small independents to run slick ordering experiences on their own domains.

Legal and contractual awareness is increasingly important. Contracts with delivery platforms can contain clauses around pricing parity, exclusivity, data usage, liability for complaints, and chargebacks that have real financial implications if not fully understood. Restaurant advisors routinely recommend that owners read the fine print carefully and, where possible, seek professional advice before committing to long‑term exclusivity or volume obligations that could limit future flexibility.

In the end, delivery apps are a tool, not a strategy in themselves. Used thoughtfully, they can bring in new customers, smooth out demand and complement a strong dine‑in and direct‑order business. Used uncritically, they can quietly erode margins, weaken your relationship with guests and leave your brand at the mercy of someone else’s algorithm, which is why a deliberate, numbers‑driven approach is essential for any owner stepping into – or staying in – the delivery game.